4D Rotation: Geometric Algebra and The Rotor

04 Apr 2022Check out this interactive article on the Rotor by Marc ten Bosch. It does a fantastic job at laying the foundations for understanding 4D rotations. An Interactive Introduction to Rotors from Geometric Algebra

Table of Contents:

- Rotation Matrices: Problems with Rotation

- Quaternions: Limitations of Axial Rotations

- The Rotor: Rotations About a Plane

- An Introduction to Geometric Algebra

- The Rotor

- Derivation of 4D Rotor Equations using GAlgebra

- My Rotor4 Code

Rotation Matrices: Problems with Rotation

Rotating a vector in 2D is pretty straightforward. To rotate a 2D vector, \(v_{xy}\), by an angle, \(\theta\), can be accomplished using the following 2D rotation matrix; where \(v'_{xy}\) is the rotated vector:

\[v'_{xy} = v_{xy} \begin{bmatrix} cos\theta & -sin\theta\\ sin\theta & cos\theta\\ \end{bmatrix}\]If we extend this to higher dimensions, we run into a problem. Euler rotations are non-commutative. Each plane of rotation is applied in turn. As each rotation is applied one after another, two planes of rotation can align themselves parallel to one another. This results in a degree of rotation being lost. This is known as gimbal lock. I would recommend watching this video for a more detailed explanation.

Quaternions: Limitations of Axial Rotations

In 3D we avoid gimbal lock by applying a single rotation, defined by a single axis. A quaternion is defined by 3 components: The \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) vector components that define axis of rotation, and \(w\), which essentially defines the axis of rotation.

In 3D quaternions work really well. However, quaternions only work in 3D. To understand why, consider a 2D square lying in the \(xy\) plane. Generally, if we were to rotate this, we would consider a rotation about the \(z\) axis. But this makes no sense... why would we leave the dimensions we are in to rotate the object. It makes much more sense to consider a rotation about the \(xy\) plane. Axial rotations become a problem in higher dimensions, i.e 4D, where there are 6 planes of rotation, which cannot be defined by axial rotations.

The Rotor: Rotations About a Plane

The rotor is an entity from geometric algebra. It is very similar to the quaternion, but rather that considering a rotation about an axis, it considers a rotation about a plane.

An Introduction to Geometric Algebra

Multivectors

A geometric space is populated by multivectors. In 4D there are five multivectors distinguished by their grade.

The Bivector and the Wedge Product

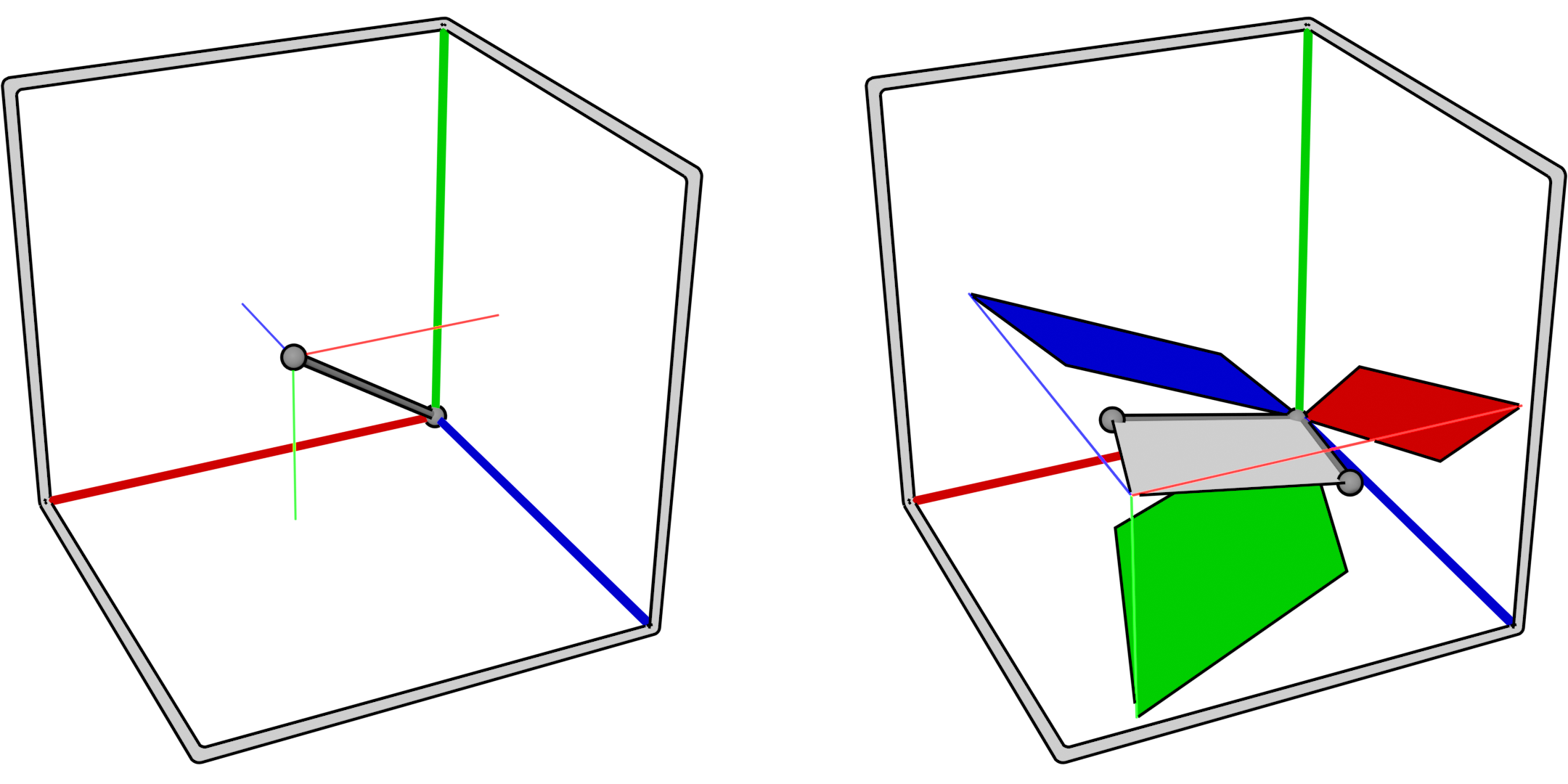

Multivectors can be added and subtracted from one another. They are associative, distributive and anti-commutative. It is defined by its orientation in space and the area of the parallelogram formed by the two vectors. The bivector \(B_{ab}\) is also defined by a direction, from vector \(a\) to vector \(b\). A bivector then follows the anti-commutative property such that: \(B_{ab} = -B_{ba}\)

A bivector is essentially a parallelogram in space defining a direction of rotation and is the basis for the rotor.

The cross product of two vectors produces a perpendicular vector with magnitude equal to the area of the parallelogram of two vectors. The wedge product (also known as the outer product) is similar to the cross product, but does not define a perpendicular vector, and instead defines the area of a bivector formed by two vectors (equal to the area of the parallelogram between the two vectors).

\[a \wedge b = B_{ab}\]For more information on multivectors head over to the euclidean space.

Multiplying Multivectors and the Geometric Product

Multivectors can be multiplied using the geometric product. The geometric product is a combination of the inner and outer product (dot and wedge products).

\[a * b = a \cdot b + a \wedge b\]Two multiply multivectors in code, we need to break down multivectors into their components, like how you may break down a 3D vector into it's \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) components. Multivectors can be broken down into projections onto their basis blades. For a vector, that means projecting each component onto it's corresponding axes (breaking it down into other vectors). For a bivector, that means projecting it onto each plane making up the vector space. In 3D that would be the \(xy\), \(xz\) and \(yz\) planes. This is shown in the following example with a vector \(v\) and bivector \(b\).

\[v = v_x + v_y + v_z\] \[b = b_{xy} + b_{xz} + b_{yz}\]

With the use of a multiplication table, the projections of multivectors can be multiplied together. The geometric product of two multivector components produces a new multivector component. These components can then be grouped together to produce the geometric product of two multivectors. For example, here would be how you would multiply two vectors using the geometric product:

\[a = a_x + a_y + a_z \\ b = b_x + b_y + b_z \\\] \[a*b = \\+ (a_x * b_x + a_x * b_y + a_x * b_z) e_x \\ + (a_y * b_x + a_y * b_y + a_y * b_z) e_y \\ + (a_z * b_x + a_z * b_y + a_z * b_z) e_z \\\] \[a*b = \\+ (e + e_{xy} - e_{zx}) e_x \\ + (-e_{xy} + e + e_{yz}) e_y \\ + (e_{zx} - e_{yz} + e) e_z \\\]The Rotor

In geometric algebra the plane to rotate about is defined by a bivector \(b\): The parallelogram formed by two vectors. The amount of rotation is defined by a scalar \(s\), and in 4D the rotor utilises a pseudo scalar \(p\) as a normalisation component. Therefore a 4D rotor is defined as:

\[R = s + b + p\]And a reversed rotor is defined as:

\[R^{\dagger} = s - b - p\]To rotate a vector \(v\) we use the sandwich geometric product. This is based on the principle that two reflections form a rotation. Check out mathoma's series on geometric algebra for a really good explanation of this stuff. The rotor vector sandwich product is as follows:

\[v' = R v R^{\dagger}\]To apply multiple rotations to a vector, rotors can be multiplied together using the geometric product to produce a new rotor.

\[v' = R_a R_b v R_a^{\dagger} R_b^{\dagger} = (R_a R_b) v (R_a R_b)^{\dagger} = R_{ab} v R_{ab}^{\dagger}\]Derivation of 4D Rotor Equations using GAlgebra

The rotor product equations can be derived using GAlgebra, a python package for symbolic calculus over geometric algebra.

Setting up the vector space:

from sympy import symbols

from galgebra.ga import Ga

from galgebra.printer import Format

Format(Fmode = False, Dmode = True)

s4coords = (x,y,z,w) = symbols('x y z w', real=True)

s4 = Ga('e',

g=[1,1,1,1],

coords=s4coords)

Deriving the rotor vector sandwich product as a closed form expression

a = s4.mv('a','vector')

s = s4.mv('s', 'scalar')

b = s4.mv('b','bivector')

p = s4.mv('p', 'pseudo')

rotor = s + b + p

(rotor * a * rotor.rev()).Fmt(3)

Deriving the rotor rotor product

a_s = s4.mv('a_s', 'scalar')

a_b = s4.mv('a_b','bivector')

a_p = s4.mv('a_p', 'pseudo')

rotor_a = a_s + a_b + a_p

b_s = s4.mv('b_s', 'scalar')

b_b = s4.mv('b_b','bivector')

b_p = s4.mv('b_p', 'pseudo')

rotor_b = b_s + b_b + b_p

(rotor_a * rotor_b).Fmt(3)

My Rotor4 Code

My code for a 4D rotor and 4D bivector, written in C# can be found here. This is incomplete and does have several problems. I will publish the fully working rotor code upon the release of 4D Games.